Beyond the blackout: are power distributors underestimating the effectiveness of their backup communications?

Beyond the blackout: are power distributors underestimating the effectiveness of their backup communications?

When the power goes out, communication becomes everything.

The power distribution network — the “last mile” of the grid — is what connects generation and transmission infrastructure directly to homes, businesses and critical services. It’s also the most visible and immediate part of the grid to communities. And when it fails, the ability to communicate effectively can be the difference between rapid containment and recovery and widespread disruption and chaos.

When the electricity gets knocked out, transport systems grind to a halt and hospitals seize up; daily commerce is thrown into disarray. With a frightening amount of everyday life, business and healthcare relying on access to the internet, it’s never been more critical for power networks to have access to resilient “always-on” communications systems. Everything from hospital ventilators to digital payment systems relies on uninterrupted power.

Power networks, particularly in Europe, are still inclined to rely on LTE and satellite systems for alternate communications in an emergency. But Tom Pope, Product Manager at Barrett Communications, warns that these are also vulnerable in a disaster.

When everything stops working

“In the event of a downed distribution line, pump failure or data system outage, the ability to communicate isn’t just operational — it’s existential,” says Pope. “Suddenly nothing works, and in that disaster scenario, power network management and field operators must be able to coordinate with each other, with emergency services and with their local community to maintain control of the situation.”

The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina brought into sharp focus just how catastrophic communications breakdowns can be. When Katrina reached the US Gulf Coast in August 2005, storm surges and winds exceeding 125 mph destroyed major transmission lines, substations, and local distribution infrastructure. In New Orleans, the electrical grid collapsed almost completely, disabling many cell towers, switching stations, and public safety communications systems and leaving entire regions unable to send or receive information.

In the critical first hours of response, the weakness of emergency radio systems was exposed as they relied on the same infrastructure that went offline – and responders were left without reliable channels to coordinate rescue and recovery operations, compounding the human and economic toll.

Two decades later, massive blackouts described as “first of their kind” cut power for 60 million people in Spain and Portugal and once again, utility communications were thrust in the spotlight and, once again found to be lacking.

“Power systems are highly complex and getting increasingly so,” says Pope. “You now have different power sources being integrated into the grid – solar and wind – and these have different dynamics than traditional sources. At the same time, there is increasing climate instability. Storms, fires, floods and heatwaves are striking more frequently and with greater intensity, and cyber attack threats are also escalating.”

Why current emergency communications aren’t enough

Fibre optic networks and LTE are often relied on as the preferred method of communication in an emergency response plan, but these are both vulnerable to physical damage from weather, a fire or an earthquake. LTE has issues with reliability – coverage can be patchy especially when roaming. LTE also presents challenges with interoperability between devices.

An LTE network can be vulnerable to jamming or intentional blocking, as well as unintentional interference from other radio frequencies, which could take the network down.

While they can be powerful, satellite systems are not failproof. “Even though satellites orbit independently, ground terminals and gateways require local power to operate and if they are knocked out then these systems are useless,” says Pope. “In addition, satellite bandwidth is finite and shared among many users. A sudden surge in traffic can quickly overload satellite links, resulting in higher latency and potential jitters.”

That’s why, Pope says, utilities should be layering satellite with infrastructure-independent technologies like HF radio, which are interoperable with Terrestrial Trunked Radio (TETRA) networks — the standard used by many emergency services and utility operators.

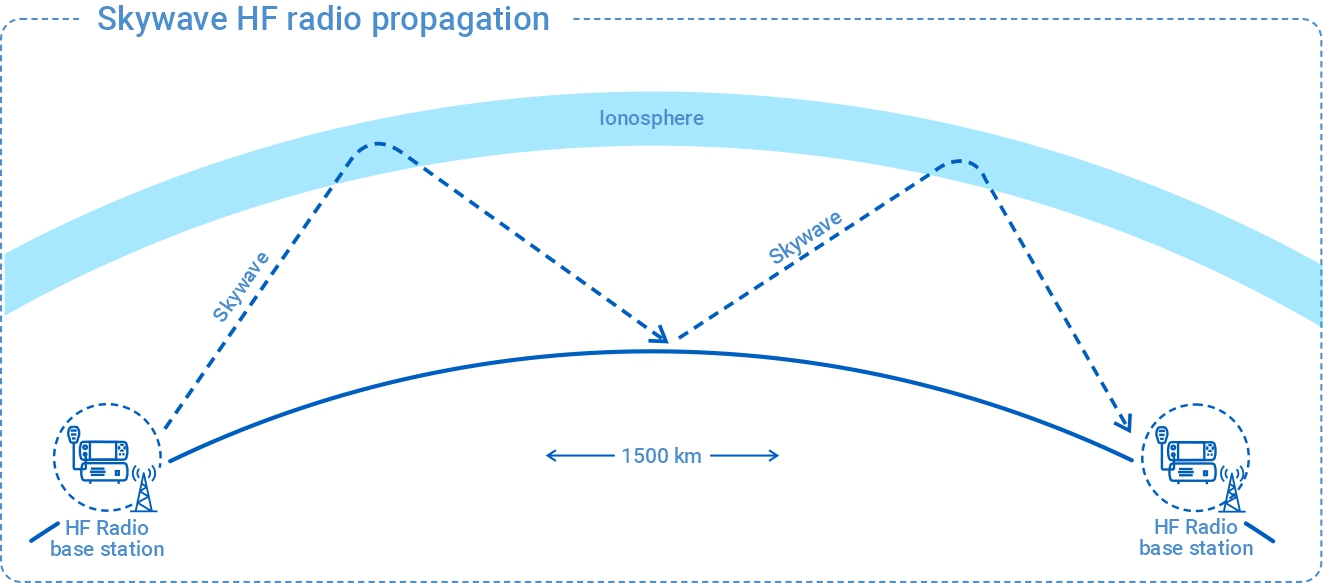

Unlike conventional mobile or fibre networks, HF radio doesn’t depend on external infrastructure. It uses skywave propagation to bounce signals off the ionosphere, enabling long-range communications – (up to 3,000 km) even in remote or compromised environments.